Unlocking non-fungible token accounting for enterprises

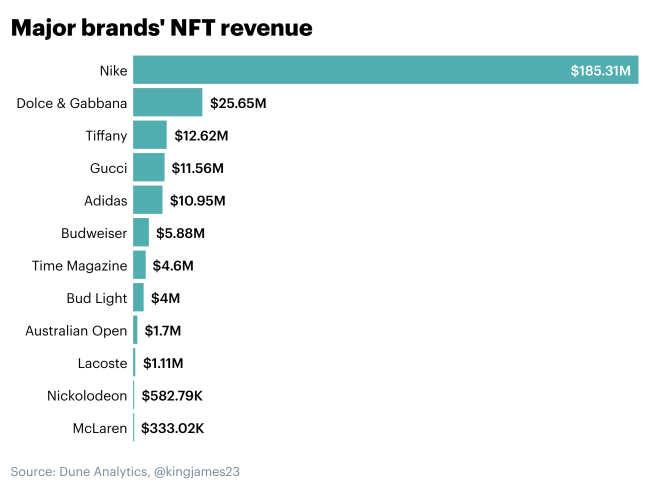

Consumer interest in NFTs (non-fungible tokens) has soared over the past couple of years, and enterprises are widely adopting NFTs as new means to generate publicity, and unlock novel revenue streams. By using NFTs, major brands such as Nike, Dolce & Gabbana, Tiffany’s, Gucci, Adidas, Time Magazine, and Bud Light have generated millions of dollars in revenue.

As existing players and new entrants expand their NFT strategies, there are technical accounting challenges and considerations that must be considered. Whether for simply investing in NFTs (Visa bought a CryptoPunk in August 2021 for $150,000, for example) or as a creator, here are a few of the key points that NFT enterprises should consider.

Revenue Recognition

In many instances, companies sell NFTs through a marketplace such as OpenSea, Solanart, or Magic Eden. These marketplaces function as an intermediary between the NFT creators and buyers. In these cases, the parties involved must determine who has control of the NFT at the time of sale to the end-user in order to determine which party is the principal, and if applicable, which party is the agent.

If the creator has control of the NFT before it is transferred to the end-user, the creator is the principal in the transaction. When the creator is the principal, the creator recognizes gross revenue in the amount paid by the end-user and separately recognizes the cost of the fees paid to the marketplace to facilitate the transaction. The marketplace, or the agent that facilitates the transaction, recognizes revenue based on the amount received from the creator in order to facilitate the transaction between the creator and end-user.

However, if the marketplace has control of the NFT at the time it is transferred to the end-user, the marketplace becomes the principal. When the marketplace is the principal, the marketplace recognizes gross revenue based on the amount paid by the end-user, and in a separate transaction it recognizes the cost of the amount paid to the creator. The creator will recognize revenue based on the amount received from the marketplace, not the gross amount paid by the end-user.

Creators and issuers of NFTs also need to evaluate if the revenue recorded from the NFT transaction is subject to the ASC 606 – Revenue Recognition standard. Creators that sell NFTs represent a contract with the end-user, and the sale of NFT is part of the creator’s ordinary activity. When evaluating NFT revenue under ASC 606, the creator needs to consider five aspects:

- Identify the contract

- Identify the performance obligations in the contract

- Determine the transaction price

- Allocate the transaction price

- Recognizes revenue when or as performance obligations are satisfied

NFTs are not all the same. Certain NFTs may give the owner the right of a digital image, or the right of a digital outfit to a gaming avatar, while others may work as subscriptions giving the owner the right to attend closed events or access paywalled content. There are limitless use cases of NFTs.

As creators evaluate the ASC 606 criteria above, they need to take into consideration each NFT, or NFT project, individually. These considerations not only apply to primary revenue (initial sales) but also to royalty revenue (secondary sales). In some cases, secondary sales can be even more material than primary sales. For example, Nike’s NFT primary and secondary sales are approximately $93 million and $92 million respectively as of August 2022.

Fair Value and Impairment

The uniqueness (or “non-fungibility”) of NFTs is what makes them popular, but it is also what makes them difficult to value. The value of each NFT is based on its specific attributes, scarcity, and distribution channel.

The value of the NFT is determined by a transaction between a willing buyer and seller. Often, this transaction involves the exchange of cryptocurrency like ETH or SOL. When cryptocurrency is exchanged in the transaction, the fair value of the cryptocurrency at the time of the transaction can be used to establish the initial value of the NFT. For example, if I buy an NFT for 2 ETH when the ETH price is $1,500, the initial value of the NFT is $3,000. If the price of ETH decreases to $1,000 after the transaction takes place, it does not have any impact on the value of the NFT. The NFT needs to be valued on a standalone basis, regardless of the value of ETH, after the initial transaction.

The ongoing valuation of NFT is the most difficult part of this process. There are not many companies today that specialize in NFT valuation because we are still in the initial stages of the industry. One option is to identify sales of similar NFTs in the market (or look at the “floor price,” or the lowest current price for NFTs of a given project). However, as we mentioned above, NFTs can be unique, especially when it comes to digital art, and there may not be a useable price comparison available.

There is no specific GAAP guidance today on how to treat NFTs and the valuation methodology to be followed. Based on the current GAAP guidance, NFTs fall under the definition of ASC 350, Intangible – Goodwill and Other: assets (not including financial assets) that lack physical substance. Within ASC 350, the holder needs to determine if the NFT has a finite or indefinite life. For example, NFTs created for the purpose of digital art will likely have an indefinite life.

ASC 35-30-35-4 says that if no legal, regulatory, contractual, competitive, economic, or other factors limit the useful life of an intangible asset to the reporting entity, the intangible asset should be classified as an indefinite-lived asset. Indefinite-lived intangible assets are not subject to amortization. Instead, it should be assessed for impairment annually, or more frequently when circumstances indicate that it is more likely than not that the asset is impaired.

It is also important to note that the digital asset industry is volatile, and prices can change significantly in a brief period. What the last buyer paid for the NFT can give an indication of its value, but the next buyer could be willing to spend less, which would be indicative of impairment in the case the NFT is identified as an indefinite-lived asset. Again, what makes NFT popular is also what makes it hard to evaluate for impairment.

Amortization

Companies may determine that their NFTs have a finite life. When making this determination, companies need to consider the period over which the NFT will contribute to the cash flow of the companies. If the company decides the cash flow of the NFT has a foreseeable limit, it is likely that the NFT will be classified as a finite-lived asset. For example, an NFT that gives the user the ability to have digital accessories in a game will probably have a foreseeable limit in cash flows because games become outdated over time when users switch to the next popular game. The same could be applied to NFTs that give users entrance to a specific event.

When NFTs are classified as finite-lived assets, companies need to amortize the NFT based on its useful life. The amortization will decrease the value of the intangible asset in the balance sheet and recognize an expense in the income statement. Like depreciation, companies can select methods that best fit their situation when applying amortization.

When considering the useful life of the asset, companies need to know the purpose of the NFT, who the end-user target is, the rights that are transferred to the end-user, and the estimated cash flow that the NFT will generate in the future. Companies should consider the factors outlined in FASB ASC 350-30-35-3 when analyzing the life of intangible assets.

Cost

In addition to revenue, valuation, and amortization, companies must also determine how to account for the cost of developing NFTs. It is likely that NFT development costs will not fall under ASC 330, Inventory, because generally, NFTs are related to digital rights and not physical property.

In most cases, costs incurred from developing NFTs will fall under the following GAAP codifications: 1) ASC 350-40, Internal-Use Software; 2) ASC 985-20, Costs of Software to be Sold, Leased, or Marketed. What determines which codification to follow is whether the end-user will own the final software or not.

Certain NFTs give the user the right to use digital items in the metaverse such as games. These items are only accessible online and hosted by the developer. In this scenario, the end-user does not have possession of the software. Therefore, the NFT development cost would likely fall under ASC 350-40. Under ASC 350-40, certain costs incurred during the development of the NFT are capitalized.

If the end-user has possession of the software upon NFT purchase, the costs related to developing the NFT would fall under ASC 950-20. Under ASC 985-20, most costs incurred during the development of the NFT are considered research and development until the technology is fully established. These costs will be expensed as incurred.

To make the right determination on cost treatment, companies need to have a good understanding of the NFTs that are being developed, including the rights that are being transferred to the end-user upon purchase, the intellectual property being developed, and the different costs being incurred during the development process.

To see learn more about our solutions for enterprise NFT accounting, contact us here